(Continued from Part 2)

Britain's air strategy was based on what is known as "strategic bombing", i.e., bombing aimed at reducing the enemy country's infrastructure, as distinct from tactical bombing in support of specific military operations.

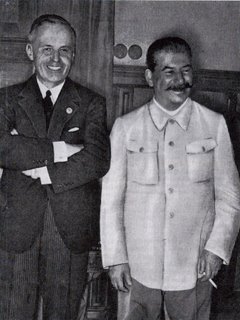

The end of appeasement: the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, 1939

Pictured here: German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop and Joseph Stalin

However, Britain's actual air force was not prepared to undertake such an effort. Record writes:

Indeed, the strength of the RAF’s ideological commitment to strategic bombing stood in stark contrast to its inability to provide convincing answers to such basic questions as what targets to bomb, how to reach them, chances of hitting them, how hard to hit them, how to determine damage inflicted, and what effect on German morale and industry?

Two famous names appear in Record's analysis in this connection. One is Charles Lindberg, darling of the isolationist, pro-German America First movement prior to the Pearl Harbor attack. The other is Winston Churchill, idol of the neocons:

The misreading of the Nazi air threat stemmed from failure to appreciate, especially in Britain, that German air power was being developed primarily for purposes other than strategic bombardment, and from deliberate strategic deception by Berlin and such influential American dupes as Charles A. Lindberg, a pro-Nazi defeatist who trumpeted German air power’s irresistibility to British, French, and American audiences.

I should introject here that the grotesque misuse of labels like "defeatist" by today's Republican supporters of the Iraq War does not mean that the terms have no legitimate usages. Record's description of Lindberg as "a pro-Nazi defeatist" is dead accurate. He continues:

The assumption was that Germany would attempt a knock-out strike against London, and as early as 1934 Winston Churchill, a persistent purveyor of inflated estimates of German air strength, argued that Germany was approaching air parity with Britain and would have three times the RAF’s strength by 1937. On the eve of Munich, Lindberg’s widely reported view was that “Germany now has the means of destroying London, Paris, and Praha [Prague] if she wishes to do so. England and France together do not have enough modern planes for effective defense.” (On the eve of the Munich Conference British intelligence estimated that Germany had a total of 1,963 combat-ready fighters, bombers, and dive bombers, when Germany actually fielded a total of only 1,194.) ...

Germany, in fact, had nothing of the sort of air capacity Lindberg claimed. A fleet of long-range four-engine bombers lay beyond Germany’s technical and industrial reach in the 1930s, and strategic bombardment was, in any event, alien to the kind of war the Germans planned to fight.

Charles Lindberg at America First Rally

"The three most important groups which have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration." - Lindberg 09/11/1941

Overestimating the enemy's capabilities can lead to just as bad decisions and underestimating them. (I'm trying to avoid any direct analogies to the present, so I will resist the temptation to point out how overestimating the weapons capabilities of an enemy country has more recently led to bad decisions with disastrous results.)

Record also discusses the role of public opinion in Britain and France, which had more immediate effect on their governments' policies than did German public opinion on theirs. It's one of the greatest strenths of democracy, perhaps its greatest benefit, is that ordinary voters and citizens and working people are just not as much fascinated by the prospects of war than their leaders and corporate barons and the country-club set often are. That was true in Britain and France in the 1930s, as well - though to the extent that it led to underestimating the threat from Hitler Germany, the healthy instinct in this case may not have produced the healthiest policy. As the Biblical proverb says, there's a time for peace and a time for war.

Record observes:

Not until 1939, after Hitler violently breached the Munich Agreement with his invasion of the remainder of Czechoslovakia, did British and French public opinion harden against Hitler to the point where it was prepared to risk war to prevent further German expansion. ...

The combination of war trauma induced by the experience of 1914-18 and sympathy toward a Versailles-wronged Germany effectively precluded any British government from carrying the country into war with Germany until Hitler clearly revealed his aggressive intentions beyond Germanic Europe. It is improbable that even the eloquent, Nazi-despising Churchill, had he been prime minister in 1938, could have mobilized public opinion for war with Hitler over the fate of Germans in a mistakenly created country that Britain was in no position to save.

Record also recalls that Germany's policy prior to Pearl Harbor was to try to avoid direct provocations of the United States. And the US options were also restricted by British and French policies. His summary of Franklin Roosevelt's position is a good one:

Roosevelt, who from the beginning had reservations about the wisdom of Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement, grasped the nature and severity of the Nazi threat long before he was politically able to do much about it. By the end of 1937, he was persuaded that the Anti-Comintern Pact between Germany, Japan, and Italy constituted a secret offensive-defensive alliance aimed at world conquest, and though he subsequently flirted with appeasement because Chamberlain seemed committed to it, the Munich Agreement and the bloody November 1938 Nazi anti-Jewish pogrom known as Kristallnacht convinced Roosevelt that Hitler’s aims were unlimited and that Nazi Germany could be stopped only by credibly threatened force. ...

It is testimony to the isolationists’ grip on the Congress (as well as Capitol Hill’s determination to reverse what it saw as a growing Executive Branch accretion of power at the expense of the Legislative Branch) that the Senate rejected Roosevelt’s personal pleas to loosen the provisions of the Neutrality Act until after war broke out in Europe in September 1939 and did not repeal the key provisions of the act until the eve of Pearl Harbor. (Congress did not authorize conscription until September 1940 — after the fall of France and the Low Countries, and amazingly, the House of Representatives voted to renew authorization for conscription by only one vote in August 1941 - 2 months after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and only 4 months before Pearl Harbor.)

Record's account also stresses an important point about the Soviet Union, one that has often been lost in the mists of Cold War polemics. And that is, Britain and France also thought that by the appeasement policy toward Germany in the West, they would encourage Germany to direct any further acts of military aggression eastward toward the Soviet Union. In Cold War Soviet accounts, this came across as a central motivation of the appeasement policy.

For instance, in a Soviet-era biography, Winston Churchill (1978) by V.G. Trukhanovsky, we read the following description of the British perspective leading up to the Munich Conference of 1938:

Neville Chamberlain, a man of very limited intellectual capabilities (and who, like all such people when in high public office, vastly overrated his talents), thought that he had found a way of killing two birds with one stone. He supposed that Germany should be egged on into a war against the Soviet Union and that, as a result of this war, the USSR would be destroyed or on the verge of collapse, and that Germany would so deplete her resources that she would lose the capacity to fight Britain for the hegemony of Europe. In order to arrange such a war, Chamberlain was prepared to make enormous concessions to Germany so as to strengthen her politically, economically and militarily. ...

As early as 1935, when the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, visited Moscow, Soviet leaders told him that it was dangerous to think that Germany would definitely strike against the USSR, while Britain remained on the sidelines: "The guns might start firing in quite a different direction." This piece of intelligent advice, like many other, similar warnings issued by the USSR, was not understood in the West. (my emphasis)

While distortion can be created by stressing one factor at the expense of all the others, as the author just quoted does, in reality Soviet leaders had every reason to be suspicious. As Record points out, if there were going to be an effective anti-Hitler coalition in the mid-1930s, a partnership between Soviet Russia and France would have been a necessary component of that:

Russia and France had been allies against Imperial Germany, and the Soviet Union in the 1930s constituted the only great power east of Germany. It fielded the largest standing army in Europe and possessed war production potential second only to that of the United States. The same logic that underlay the Anglo-French-Russian alliance of World War I against Imperial Germany applied to stopping Hitler from plunging Europe into another world war, and this logic should have been glaringly apparent after Hitler removed any doubt over his trustworthiness and territorial intentions byinvading what remained of Czechoslovakia after Munich.

But, as discussed earlier here, there were other reasons why France and Britain were reluctant to go to war over Czechoslovakia in 1938, not least among them the lack of military preparedness to match their political strategy. Also, while in retrospect an Anglo-French alliance with the USSR against Germany over the Czechoslovakian issue in 1938 seems like a blindingly obvious idea, French and British leaders had reason to wonder whether Stalin's government could be relied upon to remove its armies and associated political influence from the areas it would have to occupy in a war to protect Czechoslovakia's borders. In hindsight, it seems obvious that it was a risk worth taking. But those were real factors at work in their decision-making.

Having said all that, Record's analysis of the results of their unwillingnessto make such and alliance is still justified:

Yet in August 1939, Stalin entered a nonaggression pact with Hitler that essentially freed German forces, once they (in conjunction with Soviet forces) had erased Poland, to attack in the West with no fear of having to wage war on a second front in the East. Stalin’s conversion from a potential ally of the West into a collaborator with Nazi Germany was the product of several factors, but primary among them was Anglo-French appeasement of Hitler and manifest fear of Communism and mistrust of the Soviet Union. Many Britons and Frenchmen believed Communism posed a greater threat to the West than Nazism, and there were in any event reasonable doubts about the Soviet Union’s value as an ally against Hitler, especially after Stalin decimated the Red Army’s officer corps in 1937-38. “It was natural for European states, especially the great imperial powers, Britain and France, to regard Soviet communism as their sworn enemy - for so it was,” observes P. M. H. Bell. “From this fact of life some took the short step to the belief that the enemies of communism were your friends, and that fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were useful bulwarks against Soviet influence. Once this notion took root, it was hard to accept that the Nazi regime was itself a threat, nearer and more dangerous than the Soviet Union.” (my emphasis)

And this latter point was also the core of Churchill's analysis of the Nazi threat. Churchill had strong anti-Soviet credentials and an arguably unrealistically hostile view of the Soviet Union. But he also recognized that Nazi Germany was a more direct and immediate threat to British and other Western interests than the USSR.

Record sums up his analysis at the end by saying that the appeasement/compromise policy failed to restrain Hitler's expansionism because Hitler was both unappeasable and undeterrable. And that the leaders of France and Britain should have understood that at the time Hitler made his demands for the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938.

Nazi book burning, 1933

He was unappeasable because his real goals were such than in the end Britain and France could not have accomodated them. Hitler showed a great deal of diplomatic and political flexibility, aa the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 1939 illustrated very dramatically. But, as Eberhard Jäckeldemonstrated in Hitlers Weltanschauung (1981), Hitler never lost sight of his two central goals: eliminating the Jews and conquering Russia.

Hitler was undeterrable because he wasn't trying to avoid war, he was seeking the right opportunity to make war for Lebensraum in the east. Nazi ideology also celebrated war as a positive good whereby the Aryan master race achieved its rightful dominance over lesser human beings.

However, saying that Hitler was undeterrable is not the same as saying he could not be contained. The point is that Britain, france and Russia could ultimately not have contained Hitler Germany witout actually *going to war*. "War," Record writes, "was thus inevitable as long as Hitler remained in power."

Here, Record gives a limited and grudging endorsement to the present-day neocons' use of this historical situation:

To repeat, because Hitler was both unappeasable and undeterrable, war could have been avoided only via Hitler’s forcible removal of from power, an option apparently not considered by London or Paris and only briefly considered by German military leaders in 1938. Beyond Hitler’s departure from power, only a preventive war that crippled German military power, collapsed the Nazi regime, or both, could have averted World War II. Given the horrors of that war, initiation of a preventive war seems retrospectively imperative, and when neo-conservatives such as Richard Perle speak of how Hitler could have been stopped before 1939, they mean forcible

regime change of precisely the kind the United States launched against Iraq in 2003. For Britain and France in the 1930s, however, a decisive preventive war against Germany was morally unacceptable, politically impossible, and militarily infeasible. Rewriting history is always easier than writing it.

But he makes a strong point that the endless use of the Hitler analogy in America's wars leads to an unrealistic view of threats:

No post-1945 foreign dictatorship bears genuine comparison to the Nazi dictatorship. The scope of Hitler’s nihilism, ambitions, and military power posed a mortal threat to Western civilization. No other authoritarian or totalitarian regime has managed to employ such a powerful military instrument in such an aggressive manner to fulfill such a horrendous agenda. Stalin had great military power but was cautious and patient; he was a realist and neither lusted for war nor discounted the strength and will of the Soviet Union’s enemies. Mao Zedong was reckless but militarily weak. Ho Chi Minh’s ambitions and fighting power were local. And Saddam Hussein was never in a position to reverse U.S. military domination of the Persian Gulf. Who but Hitler was so powerful and unappeasable and undeterrable? (my emphasis in bold)

The neocons and warmongering nationalists would argue that whatever countries are on their hit list at the moment actually do meet those criteria. Saddam Hussein, to hear the Bush Republicans tell it, was the worstest and evilest and more horibble dictator and military aggressor since Hitler, no, worse than Hitler!

Here's where good judgment comes in. Rational and responsible people need to distinguish between realistic threat evaluation and trumpted-up war propaganda.

And he concludes with dual warnings, that a menace comparable to Hitler is possible, but that there are serious risks in making every war a new war against Hitler, as the US routinely does:

The problem with seeing Hitler in Stalin, Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, and Saddam Hussein is that it reinforces the presidential tendency since 1945 to overstate threats for the purpose of rallying public and congressional opinion, and overstated threats in turn encourage resort to force in circumstances where deterrence, containment, even negotiation (from strength) might better serve long-term U.S. security interests. Threats that are, in fact, limited tend to be portrayed in Manichaean terms, thus skewing the policy choice toward military action, a policy choice hardly constrained by possession of global conventional military primacy and an inadequate understanding of the limits of that primacy.

If the 1930s reveal the danger of underestimating a security threat, the post-World War II decades contain examples of the danger of overestimating a security threat.

No comments:

Post a Comment