Review of Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism (1997) by Jan Assmann (Continued from Part 1)

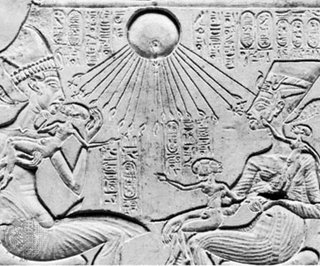

Aton the sun-god shining on Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their three daughters

There are some substantial problems with constructing historical theories about the time of Moses. Starting with the fact that outside of the traditions recorded in the Bible, there is practically no good evidence of an event corresponding to the Exodus described there. Or, for that matter, of the presence of a large number of Hebrew slaves in Egypt. At most, the archaeological record supports the idea of a gradual migration from Egypt, in which the migrants merged with other local tribes to form what eventually became the tribes of Israel.

Freud himself identifies a problem with the conventional dating of the Exodus in 1290 BCE: Ramses II was a strong Pharoah. Is it likely that he would have allowed an important population of slaves to just leave Egypt? Plagues from God and the parting of the Red Sea would help explain it, but those are phenomena which history has to forgo as explanations.

Freud argues for a date around 1350 because the political situation in Egypt then with a weakened monarchy would have been more conducive to an escape of a slave population unaided by divine curses and parting waters.

Assmann traces the roots of the Moses-Egypt discourse back to ancient writers like the Jewish historian Hosephus, who quoted the work of the Egyptian priest Manetho in the 3rd century BCE. Manetho describes a group of lepers who were expelled from Egypt and who chose a priest, Osarsiph, from Heliopolis, center of the more durable Amun-Re cult, as their leader. Osarsiph promulgates laws which bear some resemblance to the Mosaic law. Josephus regarded Manetho's story - probably with some justification - as anti-Jewish propaganda.

The academic study of Egypt in Europe gained in interest during the Renaissance,when two books to light that were taken to be good authorities of Egyptian religion, Horapello's Hieroglyphia and a mystical work called Corpus Hermeticum. An English Hebraist named John Spencer (1630-1693) made the argument that the ritual laws of the Hebrew Bible developed as reactions against Egyptian religion that the Hebrews rejected. Assmann uses the term "normative inversion" to describe Spencer's argument. In Spencer's view, the influence of Egyptian religion on early Hebrew religion was powerful but in a negative, mirror-image kind of way.

A related argument had been offered by the Jewish scholar and rabbi Moses Maimondies (1135-1204), which Spencer drew upon to some extent. Assmann summarizes Spencer's accomplishment for the study of Moses and the Hebrew Bible as follows:

Spencer's work proved ground-breaking in two different respects. First, it is remarkable that he investigated historical origins [of the Jewish religion] at all, since [Christian] orthodoxy would have clung to the notion of revelation. ... Second, his work proved ground-breaking in that it revealed Egypt as the origin of most of the legal institutions of Moses. He certainly went much too far in tracing almost everything back to Egypt, but by doing so he collected virtually all the information that in his time was available on Ancient Egyptian religion and civilization.

An English contemporary of Spencer's, Ralph Cudworth (1617-1688), was the author of a respected work with the modest title of True Intellectual System of the Universe. Cudworth tried to explore what Moses' Egyptian education might have included. He was also fond of the idea than an original monotheism had preceded all polytheistic religions.

Relying on classical sources, Cudworth elaborated one of the themes which became important in the Moses-Egypt discourse that Egyptian hieroglyphics were a secret language, meant for those who could understand the higher, inner truths of the religion. In his construction, Mo' education could have involved initiation into the secret knowledge and symbols of Egyptian religion.

One of the virtues of Assmann's book is that he reminds us how earlier scholars were struggling to find answers without some critical piece of the puzzle. Hieroglyphics were not deciphered until the early19th century. And the story of Akhenaten's monotheism was also lost to history until the archaeological discoveries of the late 19th century. Breasted's highly influential (and still well-regarded) books History of Egypt appeared in 1905 and Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt in 1912. (Freud also relied heavily on a later book of The Dawn of Conscience [1934]).

The Moses-Egypt discourse in Europe involved a variety of themes: pantheism, natural religion, Spinoza's philosophy, secrecy in religion (an important notion in theologies), Christian theology, Deism, even linguistics. Assmann discusses a variety of thinkers who contributed to the discussion in some important way: Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), Athanesius Kircher (1601-1680), John Toland (1670-1722), Matthew Tindal (1656-1733), William Warburton (1698-1779), Karl Leonhard Reinhold (1757-1825), Goethe (1749-1832), Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805), the Freemasons, Gottfried Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781).

Assmann devotes a considerable portion of his book to Freud's ideas about Moses. Freud was clear that he was indulging in a great deal of speculation. Given the scarcity of direct evidence, that's inevitable for anyone attempting to write about Moses even now. But Assmann rightly credits Freud with moving beyond the approach of previous participant in the Moses-Egypt discourse, who had relied largely on literary traditions from classical times, i.e., secondary and tertiary or even further-removed sources. Assmann calls this the memory paradigm. He writes:

Freud operates within the paradigms of history and psychoanalysis, seeking to unearth a truth that was never remembered, but instead repressed, and which only he is able to bring forth as a shocking opposite of everything consciously remembered and transmitted. ...

Freud knew what all the others [in the Moses-Egypt discourse] did not know: that there really was a monotheistic and iconoclastic counter-religion in ancient Egypt. He was able to fill the gap that so many had tried to fill with fanciful reconstructions. If the history of this discourse, from the early oral beginnings after the breakdown of the Amarna revolution until modernity, can be reconstructed as a story of remembering and forgetting, Sigmund Freud is the one who restored the suppressed evidence, who was able to retrieve lost mem and to finally complete and rectify the picture of Egypt. ... If we look at Moses and Monotheism not from the viewpoint of Freud's but from that of the Moses/Egypt discourse, we realize that the book had to be written. The rediscovery of Akhenaten simply could not pass unnoticed by those who looked for Egyptian origins. The case of Moses had to be reopened.

Sigmund Freud with his Daughter Anna Freud (1913)

I've sketched Freud's argument in Moses and Monotheism in Part 1. Assmann gives Freud particular credit for applying the idea of psychological repression on a cultural scale, and of the return of the repressed. These are concepts that Freud and the psychoanalysts developed from their discoveries in individual psychology and medical practice. The specific idea that Moses' people murdered him has never been confirmed. But the entire Moses-Egypt discourse is an example of a cultural "return of the repressed", the rediscovery of important Egyptian influences on early Jewish religious concepts.

Assmann also sees value in one of Frued's main arguments about Moses, which was the Moses created a distinct people (eventually known as Jews) around the religion of one God. Assmann writes:

Freud's construc of Moses as the creator of his nation goes against all historical probability probability. No nation has ever been created. ...

It is precisely this construction of Moses as the creator of a nation that forms the strongest link between Freud's text and the Moses/Egypt discourse. The orthodox Jewish tradition tends to play down Moses' role in the Exodus. In the Passover Haggadah, the annual reenactment of the Exodus from Egypt in the form of a family liturgy, Moses is not even mentioned. It is not a particularly Jewish project to make Moses the creator of the Jewish nation. Rather, it is one of the presuppositions of the discourse on Moses and Egypt that is shared by all the participants, including the ancient sources. It is not "Moses the prophet" but "Moses the lawgiver" who forms the thematic focus of the discourse. For Moses the prophet, an Egyptian background is unimportant. Indeed, he will have to forget what he learned from his Egyptian mastersin order to become a faithful medium of God's messages. It is Moses the lawgiver and political creator who needs his Egyptian education. ...

God [in Freud's account] is turned from a material truth into a fact of history, but it is a different kind of history which Freud is referring to. On the plane of psychohistory, God stays inaccessibly and uncontrollably remote and powerful. Religion works its coercive power from within and from below, from the immeasurable depth of the human psyche and its "archaic heritage."

Assmann also emphasizes a valuable growing from Freud's arguments about Akhenaten's religion. Frued viewed the Amarna religion as a great intellectual achievement in history, which enunciated a highly ethical set of principles and also created a powerful framework in which the powerful human feelings of guilt could be channelled into a religious outlook and related practices.

But Freud typically found a dark side to this achievement. Akhenaten's Aton religion may well have been intellectually and spiritually superior to traditional Egyptian religion. Assmann summarizes this way:

But this time the source of intolerance is enlightenment itself. Akhenaten is shown to be a figure both of enlightenment and of intolerant despotism, forcing his universalist monotheism onto his people with violence and persecution. Freud concentrates all the counter-religious force of Biblical monotheism in Akhenaten's revolution from above. This was the origin of it all. Freud stresses (quite correctly) the fact that he is dealing with the absolutely first monotheistic, counter-religious, and exclusivistically intolerant movement of this sort in human history. ... It is this hatred brought about by Akhenaten's revolution that informs the Judeophobic texts of antiquity.

Akhenaten the monotheistic Pharoah

Akhenaten's repression is a grim foreshadowing of the later history of monotheistic religions, although it's fair to say that such active suppression of other religions has historically been far more a trait of Christianity than of its Abrahamic cousins Judaism and Islam.

Assmann also devotes a chapter to a look at the Amarna religion and in what ways other than monotheism it may have different from traditional Egyptian faiths. He argues that Amarna theology expanded the concept of creation from the traditional "primordial creation" to a concept of "continuous creation" that still impled the transcendence of Aton. Post-Amarna theology develops the concept of Amun's manifestation in the physical world, a more pantheistic/immanence notion that for Assmann provides "the 'missing link' between Ramesside [post-Amarna] theology and Greco-Egyptian religious beliefs and practices".

Assmann's Moses the Egyptian in itself part of the process of the return of the repressed in religious scholarship. There is still a great deal of resistance to the notion that Akhenaten's revolutionary monotheistic religion could have had a significant influence on the early Hebrews' ideas of God and religion. Moses the Egyptian is a reminder that the question isn't going away.

But to emphasize again, there are number of issues relevant to the discussion that are far from settled. For example, Assmann uses the incident of the Hebrews worshipping the Golden Calf as evidence of Egyptian religious influence. "The Golden Calf is an Egyptian image, the bull of Apis."

Yet one interpretation of the story of the Golden Calf incident at Sinai is that it reads the sin of King Jeroboam I back into the story of the Exodus. As described in I Kings 12: 26-33, Jeroboam, who reigned in the northern Kindgom of Israel 931-910 BCE, set up golden calves in Beth-El and Dan at places of worship to serve as images of Yahweh. That reading doesn't exclude Egyptian influence, of course. But it illustrates the uncertainties of applying present-day standards of historical evidence to that period.

Other key issues yet to be resolved, not least of them the question of when the Jewish faith came to understand Yahweh as a single, universal God. That certainly seems to have been the case after the return from Babylon, initiated by the edict of the Persian kind Cyrus the Great in 538 BCE. But the Hebrew Bible contains a number of indications that Yahweh may havbe been seen at least by many as a national god of Israel/Judah, not as a universal deity. And both the Hebrew Bible and archaological findings strongly indicate that the goddess Asheroth was also worshipped in Israel and Judah, probably as a consort of Yahweh.

Assmann's book illustrates a fascinating aspect of religious history. And it place Freud's theories in Moses and Monotheism into the context of the long-running Moses-Egypt discourse in European scholarship.

No comments:

Post a Comment