(Continued from Part 1)

What is the alternative?

Another serious flaw in McMaster's presentation is that he virtually ignores the traditional notion that strictly "military" advice should focus on the enemy's capabilities, not on the enemy's intentions. The civilian policymakers are responsible for integrating the military advice and intelligence findings with an overall policy. Ultimately, the President and the Congress are responsible for the decisions for war or peace. And the President as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces has to make the call on what military policies will be implemented.

The implicit notion underlying his conclusions that the advice of the military should be conclusive is a bad one. Even a variety of militarism.

But that doesn't mean that military leaders should be allowed to duck responsibility for their own decisions and recommendations. They have an important role to play, and the generals had their share of responsibility for the failures in Vietnam. Not least of which was their wild overoptimism in their public pronouncements and their unfounded confidence in their ability to impose a military solution by attacking North Vietnam.

Some of the Chiefs' complaints were valid. For instance, the prohibition in 1965 imposed by McNamara as SecDef on striking surface-to-air missile emplacements that were designed to be used against American aircraft while they were under construction. But even in that seemingly obvious case, it wasn't purely a military call. There was a concern that Russian technicians would be killed in those strikes. That was a political factor - with definite military implications - that had to be taken into account.

What also gets very lost in the welter of boring memos and conflicting estimates, almost all of which were based on deeply flawed assumptions about the nature of the war in Vietnam, is the more specific dynamic in the national security organizations that is going to make any President of any political persuasion extremely sensitive to public dissent by his chief national security officials against major policies of the administration. Many critics of theIraq War have rightly pointed to the sidelining of General Shinseki after he suggested prior to the invasion of Iraq that theoccupation of Iraq would require far more troops than were available or than Cheney and Bush intended to commit as an example of the lack of realism on the part of the administration.

But the very idolization of the military that has been promoted by Republicans especially, and by the Christian Right in particular, means that any administration would find it very difficult to allow senior military officials to go public with major disagreements over basic policy in a war. Conservative ideology, which McMaster's book can be used to support, holds that the military should be allowed to "fight the war to win". Even if the conservatives making the point can't give any coherent definition of what "to win" might be.

So, you have President Bush saying over and over and over again that he's giving his military commanders full discretion on how to fight the war. Anything they say they need, Bush will give it to them. The claim is bogus, at least to some degree. But conservative dogma requires him to make that pretension. And to do that, part of the trick is to make sure the generals don't present any formal proposals or advice to the President that he's not willing to accept.

It works in the Cheney-Bush administration essentially the same way in did in Johnson's, although McMaster's account obscures the way in which that process works because it is so focused on showing how the Chiefs' advice failed to get to Johnson. And it would work the same way in an Al Gore or John Edwards administration. Some Presidents will be better than others about making sure they have a wide variety of options from which to choose. But especially as long as the military is treated as a sacrosanct institution that can scarcely be criticized by an elected official, no administration is going to allow the generals to dissent publicly on major issues.

Bad "lessons of Vietnam"

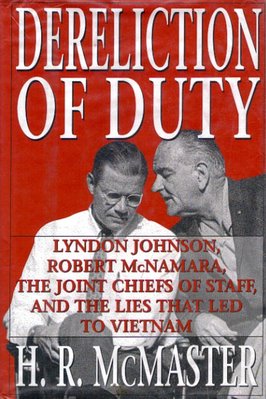

In the end, McMaster winds up arguing, again more by implications than by actual analysis, that more deference to the military advice of the JCS would have produced a signficantly better result in the Vietnam War.

But his narrative of bickering between civilian and military officials, and among the military officials themselves, doesn't establish that case. A counter-factual case could be made, and many of them have been. But McMaster's book does make such a case. It mainly points out again and again and again that civilian policymakers didn't do exactly what the JCS wanted them to do. Hey offers no alternative to the dysfunctional processes among military leaders that he describes in his narrative other than to suggest that more personal pluck on the part of the Chiefs could have overcome it. And he doesn't deal with the often poor quality of the Chiefs' advice.

Let's hope his contributions to the current Pentagon study on the Iraq War are more substantive than suggesting that we just trust our infallible generals and "unleash the military".

Links:

Scott Ritter has some caustic comments about McMaster's advocacy of the Pentagon's current counterinsurgency approach in Iraq in The military's recruiting problem Alternet.org 01/19/06

See also News Briefing with Col. H.R. McMaster 01/27/06 DOD Web site

No comments:

Post a Comment