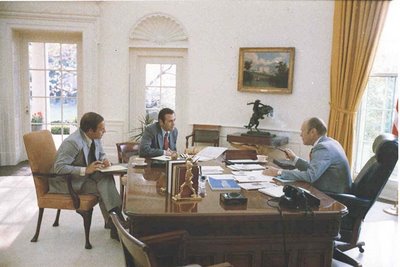

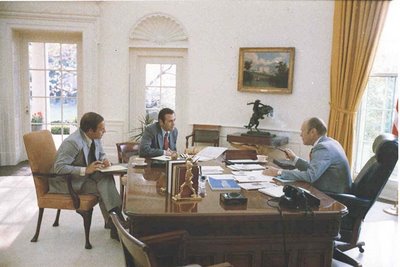

President Ford (r) meeting in the Oval Office with Dick Cheney (l) and Rummy (c)

Seeing the obituary tributes in the press to Gerald Ford, pre-written to "accentuate the positive" and to be inoffensive to Republican Party conventional wisdom, made me think more specifically about the Ford administration. This is a case where the good ole days were much better than they used to be.

So, yes, I'm taking the "Bah, humbug!" approach on the late President Ford's career.

I looked up some contemporary articles in the New York Review of Books (archive is behind subscription, unfortunately). Ah, the memories!

In Just Plain Jerry by Nicholas von Hoffman New York Review of Books 09/19/74 issue, an article from just after Ford assumed the Presidency, Von Hoffman reminds us of one of the seedier episodes in Ford's career, his attempt to impeach liberal Supreme Court Justice William Douglas:

Nevertheless, the formal biographies in both The New York Times and The Washington Post omit discussion of Ford's attempt to impeach Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas for frisking about with a twenty-three-year-old girl. The formal charges Ford laid against Douglas were hardly more serious than that, involving as they did publication of an excerpt of a book in a magazine containing dirty pitchers and an innocent connection with a foundation that may or may not have had dirty money in its treasury.

I.F. Stone also wrote about newly-installed President Ford in The Fix New York Review of Books 09/12/74 (10/03/74 issue).

He begins by criticizing the deal that Ford made with outgoing President Nixon to allow Nixon to control access to the Nixon White House tapes during his lifetime and even to destroy any he chose after five years. Fortunately, this agreement was later set aside. Stone reported on Ford's appearance before the Senate Rules Committee during which he testified about the Nixon tapes, suggesting he would be opposed to allowing Nixon to suppress them:

This is of a piece with [Ford's] conduct on the pardon. He gave the Senate committee and the country the clear impression, without saying so directly, in that disingenuous style of the Nixon and Lyndon Johnson eras, that he would not issue a pardon to Nixon. "I do not think the public would stand for it" has proven to be his most accurate prediction.

Ford made another implied pledge at the same hearing which also deserves more notice than it has received. "The attorney general," he said, "in my opinion, with the help and support of the American people, would be the controlling factor." This implies that the attorney general would be consulted in advance of a decision on pardon—otherwise how could his views possibly be "controlling" and how could public opinion help him block a pardon? But the attorney general said the day the Nixon pardon was announced and has repeated several times since that he was never consulted on the Nixon pardon.

If this is true, and Saxbe's press aides keep repeating it, then the attorney general was as much taken by surprise as Congress and the country. The surprise was all the stronger because at Ford's press conference of August 28 he over and over again gave the impression that he would take no action on a Nixon pardon until legal process had run its course. Yet we now learn that only two days later he disclosed to a few intimates that he had decided to pardon his predecessor. Duplicity is the only word for that sequence.

Stone's verdict of Ford's decision on the tapes was harsh:

This was Nixonism, pure and undefiled.

An honorable man in Ford's shoes before entering into his tapes agreement with Nixon would have consulted the attorney general, the special prosecutor, and the judges who have cases involving Watergate or the tapes. He would have sought the advice of Chairman Ervin of the Senate Watergate investigation committee and Chairman Rodino of the House Judiciary Committee, both of which still have outstanding subpoenas for tapes which Nixon refused to honor.

At his confirmation hearing Ford over and over again expressed disagreement with the withholding of these tapes by Nixon. That he has now acted so differently, and so covertly and so swiftly, speaks for itself about the true character of Gerald Ford. Tricky Dicky has been replaced by Foxy Ford. All this will deepen the suspicion that the pardon was part of a prenomination deal. If not, Ford could have plainly said so before the Senate committee last November instead of evading the issue with his disingenuous remark that "the public wouldn't stand for it." Was he then telling the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth—so help him the God he evokes as effusively and frequently as did Nixon before him?

Stone picked up his reporting on Ford's Presidency in Mr. Ford's Deceptions New York Review of Books 10/24/74 (11/14/74 issue). Ford appeared before the House Judiciary Committee as President to testify about his pardon of Nixon. Stone was downright scornful of the performance of the Democratic-majority Committee. The Committee, he complained, wasted time "in fulsome obeisance to His Imperial Majesty".

This is a reminder of the roots of the Democrats' style of bipartisanship, of which Joe Lieberman has become a sad caricature. The Democrats had been the majority party in Congress and held the Presidency most years from 1933 to 1974 (when Ford became President). They expected that a Republican President would have to work with the Democrats in Congress on key legislation. And they also expected to keep winning the Presidency most of the time, so they had a stake in setting a precedent of cooperation between President and Congress. In addition, still in 1974 there were many conservative Southern Democrats who would often vote with Republicans in support of conservative issues and still some moderate and even liberal Republicans (yes, liberal Republicans) who would vote with liberal Democrats on many issues. Today's Republicans have put those days behind them. But the Democrats, even though they no longer have a segregationist Southern wing to worry about, can't quite let go of that bipartisan inclination, which under Cheney and Bush translates into more "fulsome obeisance to His Imperial Majesty".

I.F. Stone is considered one of the great investigative reporters, a rapidly-disappearing phenemenon in American journalism. (Not just the "great" ones, but investigative journalism itself.) But Stone didn't do his work through the kind of "access" for which Bob Woodward sold his journalistic soul to the Cheney-Bush administration. Stone got much of his material by carefully studying public documents, such as government reports and Congressional testimony, and then teasing out connections between them. In this article, we see that process at work. Building on revelations provided by Ford himself, Stone asks some reasonable questions:

Ford says he did not make a deal. Nobody asked him what he meant by a deal. He certainly didn't make a deal in the sense of saying, "Dick, if you resign and give me the presidency, I'll pardon you for any crimes you may have committed." But in the conversation with Haig could they not very naturally and urgently have said to each other that anything would be better for the GOP and the country than a general self-pardon? Was there not a kind of political blackmail in Nixon's implied threat to pardon himself? Did Ford mention to Haig that for him to pardon Nixon would also be embarrassing in view of the position he had taken at his confirmation hearing? Was this Nixon threat "the reality" Ford said at one press conference he had to contend with when asked about his earlier implied pledged not to pardon - the pledge he dismissed as "hypothetical"?

He proceeds to elaborate on the circumstantial evidence suggesting that Ford indeed made a deal with Nixon over the pardon, which I'm convinced he did.

But would Ford actually need to keep such an agreement a secret? Stone explains, in a passage worth remembering in light of more recent circumstances:

One thing is clear, and was almost certainly brought to their attention by their lawyers in studying the pardon question. Criminal liability attaches to an agreement to grant a pardon except where the contract serves some law enforcement purpose. Section 2 of the chapter on pardons and parole in American Jurisprudence says, "Where, however, personal interest enters into the success of the contract, or the use of personal influence is contemplated, the general rule is that the contract is illegal as against public policy, and so unenforceable." A pardon tainted by fraud is revocable in the courts under a rule already old at the time of Blackstone, who wrote, "Any suppression of truth, or suggestion of falsehood, in a charter of pardon, will vitiate the whole." It may not be merely public relations or propaganda which leads Ford now to stress that the pardon was given not to help an ailing Nixon but to help an ailing country.

And in light of the sachrine homages to how Ford "healed" the nation with his Nixon pardon, Stone's following observation is worth quoting at some length:

A similarly naïve question might be asked of Ford. If he truly wanted to save the country from more divisiveness and suspicion in the wake of Watergate, why didn't he "touch all bases" before pardoning Nixon? How different the effect would have been if Ford had consulted the attorney general, as he implied he would last November, and Jaworski and the eight congressional leaders who are supposed to be consulted before any step to limit or abolish the special prosecutor's office.

How impressive, how healing it would have been if the Nixon pardon had been countersigned, as it were, by the attorney general, the special prosecutor, and the eight congressional "watchdogs" set up by his charter! How impressive indeed! But even a latter-day Hans Christian Andersen would find it hard to imagine any of these other public officials counter-signing so preposterous and unprecedented a pardon before investigation and prosecution of the Watergate affair, up to and including the Oval Office, had been completed.

To have consulted the attorney general would have been most embarrassing. Under the Code of Federal Regulations—and the Supreme Court in US v. Sirica has just held that such regulations, until repealed, have "the force of law"—a "pardon attorney" in the Department of Justice is in charge "of the receipt, investigation, and disposition of applications to the president for pardon."

The code sets up an elaborate machinery for investigating such applications. It also provides that no petition for pardon can be filed until three years after release of the petitioner from confinement, or three years after conviction if no prison sentence is imposed. But in cases of violation of "income tax laws, perjury, violation of public trust involving personal dishonesty…a waiting period of five years is usually required." That would seem to cover any and all Watergate defendants including unindicted co-conspirator Nixon.

Of course a president can pretty much do as he pleases and get away with it in exercising the pardoning power, as in many other matters. But if the White House or the attorney general had inquired of the pardon attorney, as we did, they would have been told that the present occupant of the office had never heard of a presidential pardon outside these channels, that he had asked his predecessor who took office in 1950, and that the latter too could not recall such a presidential pardon. That covers the last quarter century at least.

Stone proceeds to follow the precedent even farther back.

Ford's pardon of Nixon was precedent-setting, in more ways than one:

The only way for a president to grant a swift pardon outside these time-honored channels is by proclamation, and that is the method adopted by Ford in the case of Nixon. But those at the National Archives to whom we put the question were unable to find a single precedent for the pardon of one man by proclamation. Pardon or amnesty proclamations have mostly been issued in connection with wars and have covered a whole class of persons. The earliest was issued to reward Jean Laffite's pirates for their aid to Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812. The famous pardon and amnesty proclamations of Lincoln and Johnson were issued on special statutory authority from Congress under a law repealed in 1867.

One of the things that Ford revealed at that hearing was that Nixon had considered issuing a blanket pardon for himself and all the other Watergate criminals. Stone also focused on the fact, which Ford had revealed at the hearing, that "Nixon's main concern during his last days in office was how to avoid prosecution". That's something that we should keep in mind about the current Vice President and President. Journalists almost never mention it. But it's clear that the possibility of serious legal trouble is a major concern on their minds. (See Bush is bracing for new scrutiny: White House hiring lawyers in expectation of Democratic probes by Julie Hirschfeld Davis Chicago Tribune 12/26/06 for an exception to press silence on that matter.)

Gary Wills expressed his own dissent from Ford's nice-guy reputation in He's Not So Dumb New York Review of Books 10/16/75 issue:

He has even turned a half-joking reputation for dimwittedness to political advantage. When he performs hack work or malicious hatchet jobs—even the Douglas campaign, which lasted more than a year and sank to vicious tactics—he remains "good old Jerry" just doing someone else's dirty work. That is how members of the confirmation committee treated the affair, even though Ford renewed his Douglas trouble with unconvincing stories under oath. No one suspects him of being tortuous or Machiavellian; an engaging simplicity absolves him from ability to scheme. He intuitively plays on this. As Nixon blundered down, Ford took Pollyanna flights around the country, delivering pep talks on Republicanism. Some advised him to stay in Washington, to bone up on his future job. They did not reflect that the first thing he did, after being chosen to supplant Charles Hoeven as chairman of the Republican Conference, was to leave the country. He managed three vacations while his backers managed his coup.

He will do almost anybody's dirty work - Dirksen's, or Nixon's, or Mitchell's, or Agnew's - but he is careful to have others do his own. Even his lies before the committee were received as exercises in doomed loyalty to Nixon rather than in personal mendacity. Ford knows when to let others do the ground work for him. He only needs a wink, and then he can relax - a rare gift among politicians, who like to be doing something about their careers all the time. Ford credibly repeated that he was making no preparation to be president while Nixon fought the sheriff off. Bob Hartmann and Phil Buchen were doing the preparing. They assembled the transition teams, without Ford's formal acknowledgment (much like the "draft" campaigns for candidates, undertaken without the formal approval of their beneficiaries).

"He will do almost anybody's dirty work ... but he is careful to have others do his own." I'm sure he and Dick Cheney got along just fine.

Wills also includes the LBJ quote that I screwed up a bit in my comments to Wonky Muse's post about Ford's passing:

When he has to, [Ford] can change his story on the stand. Those who think Jerry Ford "too dumb to fart and chew gum at the same time" ... need only read the confirmation hearings to see he can maneuver inch-by-inch to save his skin.

Juan Cole recalls Ford's foreign policies in his post, Ford and Foreign Policy: Snapshots from the 1970s, Informed Comment blog 12/27/06. He writes:

All presidents make errors, and some abuses occurred on Ford's watch, though they often were initiated by [Ford's Secretary of State Henry] Kissinger. But Ford faced with no illusions the challenges of his era, of detente with the Soviet Union, continued attempts to cultivate China, the collapse of Indochina, the fall-out of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, and the beginnings of the Lebanese Civil War. Ford was right about detente, right about China, right about Arab-Israeli peace, right about avoiding a big entanglement in Angola, right to worry about nuclear proliferation (one of his worries was the increasing evidence that the Middle East had a nuclear power, Israel, and India was moving in that direction).

Ford's challengers on the Reagan Right were wrong about everything. They vastly over-estimated the military and economic strength of the Soviet Union (yes, that's Paul Wolfowitz). They wanted confrontation with China. They dismissed the Arab world as Soviet occupied territory (even though the vast majority of Arab states was US allies at that time) and urged that it be punished till it accepted Israel's territorial gains in 1967. They insisted that the Vietnam War could have been won.

But despite its illusions and Orwellian falsehoods, the Reagan Right prevailed. Ford only momentarily lost to Carter. Both of them were to lose to Reagan, who resorted to Cold War brinkmanship, private militias, death squads, offshore accounts, unconstitutional criminality, and under the table deals with Khomeini, and who created a transition out of the Cold War that left the private militias (one of them al-Qaeda) empowered to wreak destruction in the aftermath. The blowback from that Reaganesque era of private armies of the Right helped push the US after 2001 toward an incipient fascism at which Ford, the All-American, the lawyerly gentleman, the great Wolverine, must have wept daily in his twilight years.

Cole is being generous to Ford in the last sentence. And his thought may be accurate. But I don't recall hearing anything about Ford expressing any great reservations about the Cheney-Bush policies at home and abroad. Declining health may have affected his ability and willingness to do so. But Ford was a loyal Republican. And if he didn't express such doubts, well, no evidence is no evidence.

Cole is right that the difference betweenn Ford Republicans and Reagan Republicans was significant. But it's easy to overdraw that distinction. The "moderate" Republicans like Ford hardly bolted the party as it went farther and farther in the direction of rogue operations, to the point where today's Cheney-Bush foreign policy is basically one big set of rogue operations.

Ford also appointed Old Man Bush as CIA director, strenthening the Bush's dynasty's intelligence ties. Some of Old Man Bush's actions as CIA director and later in using his intelligence connections have never been adequately investigated, specifically the Iran-Contra affair and the "October surprise" deal with the Iranian theocratic government in 1980 to delay release of American hostages until after the Presidential election.

Update 12/28/06: Via Laura Rozen, I see that Ford did speak out against Dear Leader Bush's Iraq War. Although speak "out" may be the wrong term, since it was in an "embargoed" interview. God forbid that denouncing an unjust war terribly damaging to the United States should take precedent over avoiding embarassment for the Republicans in an election year. And what Bob Woodward is reporting hardly counts as a ringing denunciation. From Ford Disagreed With Bush About Invading Iraq by Bob Woodward Washington Post12/28/06:

Former president Gerald R. Ford said in an embargoed interview in July 2004 that the Iraq war was not justified. "I don't think I would have gone to war," he said a little more than a year after President Bush launched the invasion advocated and carried out by prominent veterans of Ford's own administration.

In a four-hour conversation at his house in Beaver Creek, Colo., Ford "very strongly" disagreed with the current president's justifications for invading Iraq and said he would have pushed alternatives, such as sanctions, much more vigorously. In the tape-recorded interview, Ford was critical not only of Bush but also of Vice President Cheney -- Ford's White House chief of staff -- and then-Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, who served as Ford's chief of staff and then his Pentagon chief.

"Rumsfeld and Cheney and the president made a big mistake in justifying going into the war in Iraq. They put the emphasis on weapons of mass destruction," Ford said. "And now, I've never publicly said I thought they made a mistake, but I felt very strongly it was an error in how they should justify what they were going to do."

Tags: ford, gerald ford, nixon, nixon pardon, president ford, richard nixon